The Civil War Began and Ended In One Man’s Yard

In the annals of American history, few stories are as ironically poignant as that of Wilmer McLean, a Virginia farmer who could claim—with only slight exaggeration—that the Civil War began in his front yard and ended in his front parlor.

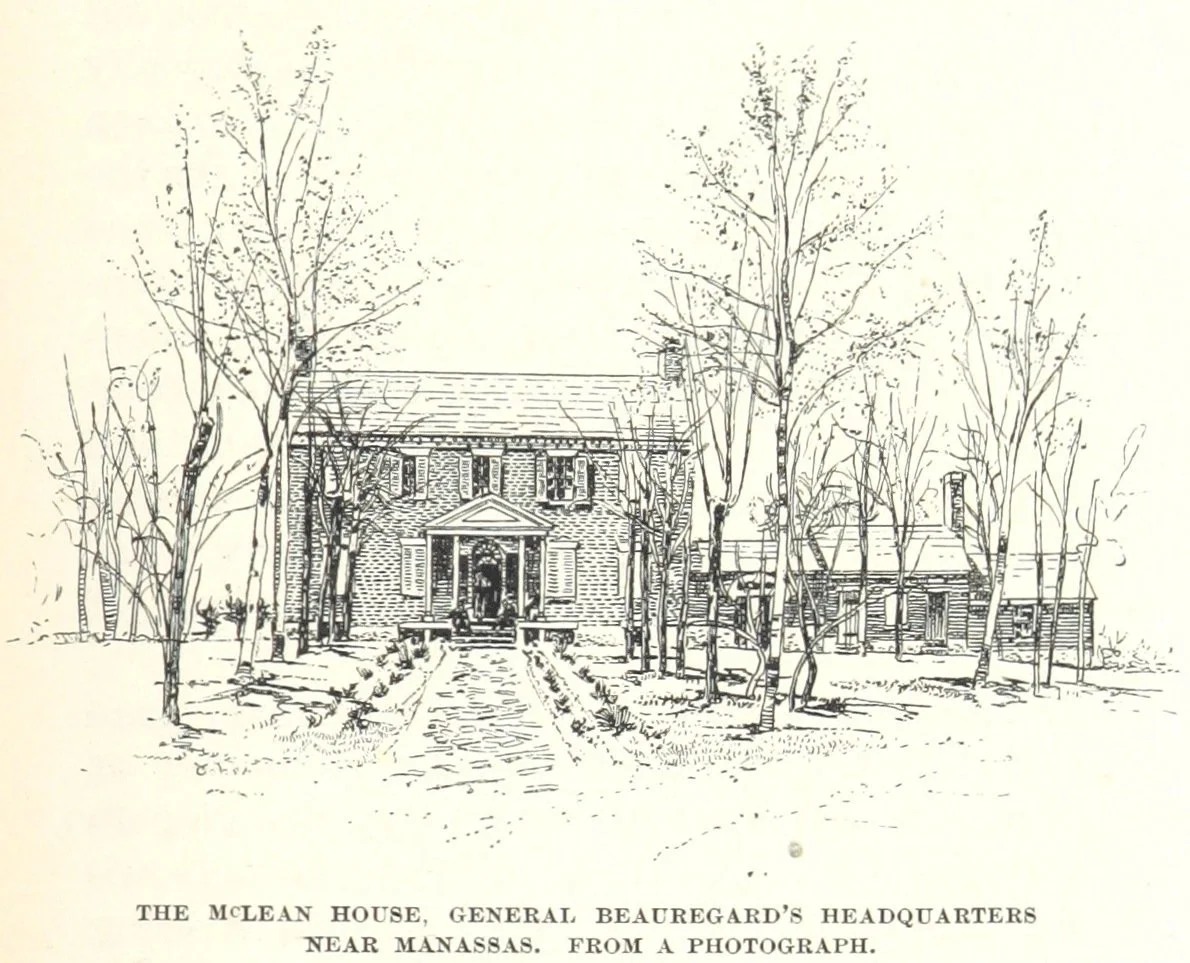

Our tale begins on July 21, 1861, near Manassas, Virginia. The Civil War was in its infancy, and the first major land battle was about to erupt. Wilmer McLean, a 47-year-old wholesale grocer, owned a farm called Yorkshire near Bull Run. As fate would have it, his property became the nerve center for Confederate forces during the First Battle of Bull Run.

That sunny Sunday morning, McLean's house was appropriated as headquarters by Confederate Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard. The peaceful Virginia countryside soon erupted in gunfire and chaos. A Union shell crashed through McLean's kitchen chimney, exploding in a soup pot and ruining the family's dinner. By day's end, the Confederates had won, but McLean's property lay in disarray, his fields trampled by soldiers and horses.

Seeking peace and safety for his family, McLean decided to move. In the spring of 1863, he relocated 120 miles south to a small village called Appomattox Court House, believing he had left the war behind.

Fast forward to April 9, 1865. The war had raged for four long years, leaving a trail of destruction across the nation. Confederate General Robert E. Lee, his army exhausted and surrounded, was seeking a place to meet with Union General Ulysses S. Grant to discuss surrender terms.

A Union officer approached McLean, now comfortably ensconced in his new home, and requested the use of his parlor for a meeting between two important generals. McLean reluctantly agreed, unaware he was about to host one of the most significant events in American history.

That afternoon, Lee arrived in his dress uniform, followed shortly by Grant in his mud-spattered field garb. In McLean's front parlor, the two generals discussed and signed the terms of surrender, effectively ending the Civil War.

As the meeting concluded, Union officers began taking furnishings from McLean's house as souvenirs. His favorite wooden table, on which the surrender document was signed, was carried off by General Sheridan, who paid McLean $20 in gold. McLean would later lament, "The war began in my front yard and ended in my front parlor."

Wilmer McLean's unique place in history serves as a poignant reminder of the war's far-reaching impact on ordinary citizens. His story encapsulates the Civil War's entire arc—from the optimistic fervor of First Bull Run to the somber resignation at Appomattox—all within the confines of one man's property.

While it's not entirely accurate to say the war started and ended in McLean's yard—the conflict's roots ran far deeper, and scattered fighting continued for weeks after Appomattox—his experience provides a compelling narrative framework for understanding the war's progression and its intrusion into the lives of civilians.

Today, McLean's Appomattox home stands as part of the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, a testament to the quirks of fate that can place ordinary people at the crossroads of history.